The Shelby County Community Theatre's Feasibility Path To Expansion

- Dec 22, 2025

- 5 min read

Shelby County Community Theatre did not arrive at the question of expansion overnight. The organization has spent nearly five decades building its place in the cultural fabric of Shelbyville, Kentucky — growing carefully, incrementally, and always in close relationship with its community.

Founded in 1977, SCCT staged its inaugural production, The Music Man, on the stage of Shelby County High School that same year. Just two years later, in 1979, the organization secured a permanent home at the corner of Eighth and Main Streets, purchasing the building for $30,500 with the help of a significant community gift. What began as a modest community theatre has since evolved into a multi-generational institution, with productions that regularly include parents, children, and grandparents across casts, crews, and audiences.

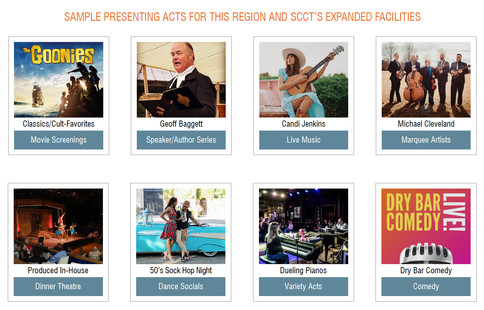

Over time, programming expanded beyond Main Stage plays and musicals to include youth productions, education programs, and the creation of the “Upstairs at 801” performance and multipurpose space. The theatre’s reputation extended well beyond Shelbyville, attracting performers and directors from Louisville, Lexington, and across central Kentucky. What remained constant, however, was the footprint of the building itself — a facility never designed to support the scale of activity it would eventually host.

By the time SCCT’s Board began exploring expansion, the organization was not struggling. It was thriving. And that distinction matters.

Growth That Created Pressure, Not Problems

From an operational perspective, SCCT’s success was measurable. Coming out of the pandemic, the organization rebounded quickly. In FY2022, SCCT produced 54 shows and generated approximately $91,315 in ticket revenue, even as average attendance remained suppressed at roughly 74 tickets per show, representing 73% of Main Stage capacity. By FY2023 and FY2024, both volume and performance had improved substantially, with 60–61 productions annually, average attendance climbing above 100 patrons per performance, and capacity sold averaging over 90% across venues.

Main Stage performances — housed in a 134-seat theatre — were routinely selling out. Added performances, intended as a pressure valve, were also nearing capacity. Utilization data told a similar story. Prior to the pandemic, Main Stage usage peaked near 80% occupancy. By FY2023–FY2024, utilization had stabilized between 57% and 80%, leaving little room to add additional productions without displacing rehearsals, educational programs, or community uses.

The Upstairs space, by contrast, showed utilization between 20% and 45%, not because of lack of interest, but because of functional limitations: inadequate AV infrastructure, limited accessibility, and the absence of meeting-ready amenities. The building, in other words, was doing everything it reasonably could — and no more.

This is a critical moment for nonprofit performing arts organizations. Growth of this kind creates friction not because the mission is failing, but because infrastructure has not kept pace.

Asking the Right Questions Before Proposing Answers

SCCT’s Board understood that expansion would represent one of the most consequential decisions in the organization’s history. Rather than beginning with design concepts or capital targets, they asked a more fundamental set of questions:

Is utilization and ticket demand truly at a point where expansion is necessary?

Could strategic improvements to the existing building address these pressures?

If expansion is warranted, what scale is appropriate — and financially responsible?

And how would the organization sustain expanded operations over time?

These questions framed the feasibility study not as a justification exercise, but as a diagnostic one.

Discovery Rooted in Community and Operations

The discovery and engagement phase began with a deep look at SCCT’s history, its role within Shelbyville, and the broader regional context. Shelbyville, with a population of approximately 18,000, sits within Kentucky’s “Golden Triangle,” offering access to the Louisville and Lexington markets while maintaining a strong local identity. Audience origination data reinforced this dual role. Nearly 1,900 ticket buyers came from Shelbyville’s home zip code (40065), with significant attendance from surrounding communities and the Louisville metro area, confirming SCCT’s reach as both a hometown theatre and a regional draw.

Stakeholder interviews echoed what the data suggested. There was strong respect for SCCT’s longevity, artistic quality, and community presence — paired with consistent concern about operational strain. Interviewees emphasized the importance of preserving the theatre’s intimacy while improving backstage functionality, technical infrastructure, and accessibility. Expansion was broadly supported, but only if pursued with realism and discipline.

A community-wide survey reinforced these findings. Ninety percent of respondents agreed that SCCT should expand its facility and programming. Performing arts ranked as the county’s top cultural interest, but respondents cited sold-out performances, limited amenities, and scheduling constraints as barriers to participation. Importantly, survey participants expressed willingness to support expansion through attendance, volunteering, and donations — signaling a strong foundation of community buy-in.

What the Data Revealed

Operational analysis made clear that SCCT’s challenges were structural, not cyclical. Musicals consistently outperformed plays in ticket sales, suggesting that any growth in production volume should prioritize musical programming within limited calendar availability. Youth theatre productions and classes showed strong demand, but were constrained by space and scheduling conflicts. Rentals and community uses were possible, but difficult to accommodate without displacing core programming.

In short, the organization had reached the practical limits of what its existing facility could support. Continued growth without intervention would risk burnout, missed revenue opportunities, and diminished audience experience.

From Insight to Strategy

Rather than advancing a single expansion concept, the feasibility study focused on creating options — recognizing that flexibility is itself a form of risk management. Phased development emerged as a critical strategy, allowing SCCT to align capital investment with fundraising capacity and organizational readiness.

The study also emphasized that expansion must be paired with operational planning. A five-year pro forma demonstrated that, with an expanded and renovated campus, earned income could grow from approximately $426,000 in Year 1 to more than $639,000 by Year 5, driven by increased ticket sales, rentals, facility fees, and concessions. Combined revenues were projected to rise from roughly $597,000 to over $823,000, with earned income making up a growing share of the total — supporting a more resilient operating model.

Equally important, utilization forecasts showed that new and renovated spaces could support more than 480 annual use days by Year 5, more than doubling current activity while maintaining balanced usage across performance, education, and community functions.

Why This Work Matters

The Shelby County Community Theatre feasibility study illustrates what responsible growth looks like for nonprofit performing arts organizations. Expansion was not treated as a reward for success, but as a tool to sustain it. Decisions were grounded in data, shaped by community values, and tested against long-term operational realities.

Feasibility studies, when done well, do not promise certainty. They provide clarity. They allow organizations to move forward with eyes open — understanding not just what a building could be, but what it would require to operate, maintain, and animate it for decades to come.

For SCCT, this process created a clear, defensible path forward. For TheatreDNA, it reaffirmed a core belief: the most successful cultural facilities are those designed around organizations, not the other way around.

And that is how big cultural investments are de-risked — not by thinking smaller, but by planning smarter.